Description and structure

The STEPS project introduces an original method that aims to empower and enhance the psychosocial skills of prisoners or ex-prisoners, through their participation in virtual reality experiences, by means of which they acquire voice and become protagonists of life. The development of the psychosocial skills of prisoners, which, in our opinion, is ideally done only in an experiential way and not through preaching, is a burning issue in the education of prisoners and other populations (Beyer, 2017).

Show more

Virtual reality is perceived as a particular teaching aid (Valakas, 1999). As it is known, by using such teaching aids the educator activates more senses at the same time, clearly conveys concepts, relationships and phenomena, attracts attention and stimulates interest, represents reality. However, experts draw attention to the following (Valakas, 1999): teaching aids should be instruments of presentation, “teaching collaborators” and means of creative application; they should not used just to offer some “spectacle”. We consider virtual reality, as we described it in the subsection 3.1.1, especially suitable for all this.

The method consists of 6 virtual reality stories, the so-called rooms (their creation was described in Chapter 3.3., while their plots are presented in section 4.4.), proposing the conduct of 6 corresponding educational activities. Therefore, it is an educational programme comprising of 6 learning activities that normally takes place in an educational environment or in another place within a prison or in the premises of organizations and services that deal with the reintegration and rehabilitation of released prisoners. The stories have as central person (the so-called protagonist) male and female prisoners and ex-prisoners from various European countries. In total we have three “women’s” stories and three “men’s” stories.

The philosophy of the method is for the incarcerated or released to experience a secondary life experience, but as close as possible to the primary one, which in terms of content is not fantastic, but authentic and even comes from people living in different European countries. In this way, the prisoner/user is called to feel present in a composite, virtual world that is – ontologically only – away from the reality and to experience a “tele-presence”. So, (s)he acquires thought and reason within this “foreign” story and then (s)he is called, in a group context, to think and talk, at least, about what he felt and maybe about the role he played, even if unconsciously, in this original “virtual real life theater”. In this process, which per room is good to last up to 4 teaching hours in the same day, the user-inmate or ex-prisoner is supported through reflection and the general context to connect with positive thinking and in the long run to proceed with the transformation.

Ideal form of use of the method

Each of the 6 educational activities should be perceived as a learning experience consisting of two main parts. The first part focuses on experiencing virtual experience/VR history, while the second focuses on educational exploitation. More specifically, in the first part, trainees, incarcerated or released (for which we will henceforth use the term “users”, meaning the use of technological equipment), are properly prepared to experience the VR story. In the second part, the group engages in further activities and semi-structured discussion with the help of a facilitator in order to identify a new life role for the protagonist of the story they watched.

As we calculate the duration of an educational activity up to 3-4 teaching hours, we would say that our program can have a total duration (with the same group of trainees) of 24 hours in 6 weeks (1 room/story per week) or in 3 weeks (2 rooms/stories per week). Specifically, a four-person training team can complete the program in 6 days (better not in successive days). So if the educator receives the interest of 12 persons, (s)he should calculate about 18 days of his/her time.

It should be understood that the method is not for everyone (prisoner), because there is really no such method absolutely suitable for everyone (“one size fits all”) and it is totally acceptable that some inmates may refuse to participate or give up etc. This is often the case at the experiential learning approaches. In any case, the educator is obliged to have studied everything related to the method before applying it, as well as to his group. This, first and foremost, means that the educator must have carefully watched all the rooms on his own and that he has already drawn up a first plan for their use (Gasouka, 1999). The management of reality is in the “hand” of the educator and the educated, not in the method itself. Next section makes all this more clear.

REFERENCES

Beyer, L. N. (2017). Social and Emotional Learning and Traditionally Underserved Populations. American Youth Policy Forum.

Valakas, G. (1999). “Educational aids and educational space” in: Programme of training (Adult) Educators. Band III. EKEPIS

show less

Technical instructions

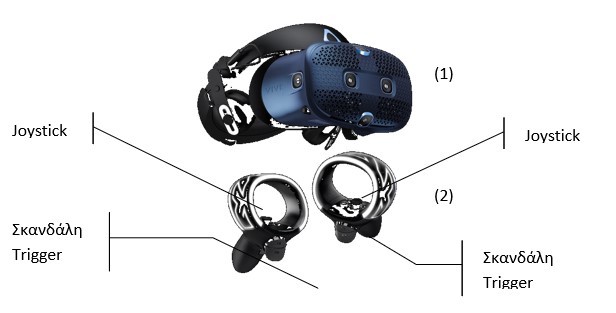

VR rooms use VIVE ™ Headset device and controllers. Although other VR devices may be used, VR Rooms are optimized for this particular set.

The student wears the headset (1) and catches the controllers (2) (L) left and (R) with the right hand respectively.

The moves of the students’ head as well as his/her moves inside the real-world are translated into viewpoint rotations and moves inside the virtual space (Rooms). The moves of the controllers are translated into the moves of a pair of red/black gloves which are the avatar of the user hands (controllers) inside the Rooms.

Show more

The student, according to the scenario, should be standing or sitting on a chair. Some students may feel some kind of dizziness by the VR system. That’s why a dedicated demo VR movie is also available, in case the teacher decides to familiarize the students to the VR headset first (suggested). The educator should always stand behind the student and take care of him/her.

Before the beginning of the first VR Room, the educator should give some basic instructions about the VR Rooms interfaces and how the user should interact with the objects and follow the scenario.

Once the student wears the Headset and handles the two controllers, the VR Room starts with the language selection screen.

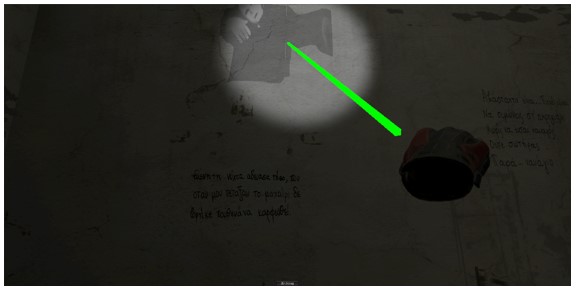

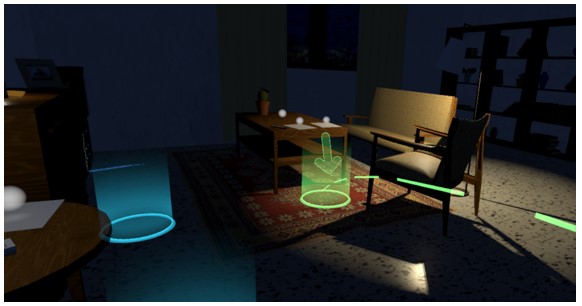

Language selection is effected through a green laser beam which the user enables by using the “gun like” trigger in the controller. After language selection, student enters the VR Rooms.

The student has two main ways to interact with the objects inside the rooms.

- By pointing with a green laser beam. To do so, the student pushes the controller’s trigger (same as in language selection) and keeps it pushed until to target to the object they want to interact with. The objects that are interacting with green laser beam are always sufficiently illuminated by a spot light in order to be distinguished from the environment.

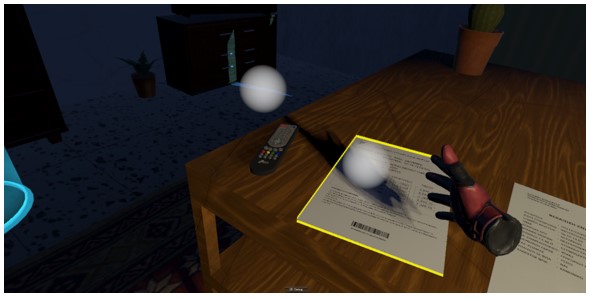

2. By catching (grabbing) an object. Some objects have an illuminating “light” ball very close to them. This “light” ball signifies that this object may be “caught” by the user. The student has to move towards the object and, when the glove (controller avatar) is very close, he can catch it with the glove by pushing the trigger.

If the user (=student) is grabbing the object, then he/she can move it, read it, in case it is a piece of paper, and in general may interact with it.

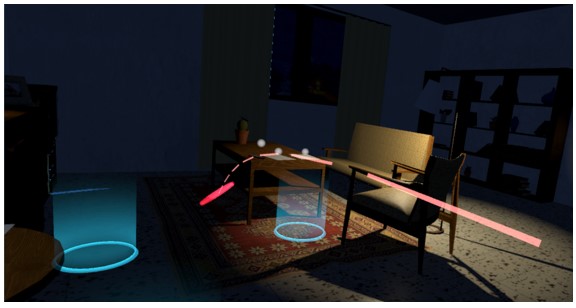

The student also is able to move inside VR Rooms, according to the scenario. In this case the user may move with “teleporting”. This is done with the joystick in the top of the VR controller. Once the joystick is pushed in front, a red curved beam appears and in the floor appear some light-blue spots (circles) showing the possible moves (teleports) the user may choose. If the red beam is matching to a light-blue spot, they are both becoming green and a green arrow is showing the exact position of teleporting.

If the user (=student) is grabbing the object, then he/she can move it, read it, in case it is a piece of paper, and in general may interact with it.

The student also is able to move inside VR Rooms, according to the scenario. In this case the user may move with “teleporting”. This is done with the joystick in the top of the VR controller. Once the joystick is pushed in front, a red curved beam appears and in the floor appear some light-blue spots (circles) showing the possible moves (teleports) the user may choose. If the red beam is matching to a light-blue spot, they are both becoming green and a green arrow is showing the exact position of teleporting.

show less

A proposal for doing the activity

In this section we describe the structure of the educational activity as a framework common for all of them. The proposed actions have an experiential profile and are inspired from the group-collaborative pedagogical approach, of which the advantages are known and especially desired by our method. However, where this is not possible, or where necessary, a personalized approach can be used. In an environment outside of a detention center, such as a group/organization/reintegration service, it is necessary to make an effort to form groups in order to enhance more social skills. Regarding the size of the group, we believe that the ideal number is 4 people. It should also be noted that the method could be used – or, in fact, it would be appropriate to be used- in a frame of cooperation between teachers and of co-teaching, that is to be connected with practices whose usefulness in education has been well documented (Oikonomou, 2016).

Show more

As already suggested, the proposed activity has a three-part structure.

The first part is called “before and during the experience of virtual reality” and is the part of the method that essentially prepares the students for the experience of virtual reality and even includes its watching. We suggest two activities. The first is entitled “Exploring the sides of myself” and is intended for the case of individual participation. The second is called “The course of my life in prison” and is intended for group use, ie in the case that a group together wants to implement this first part, accepting the waiting times that result from the existence of just a single piece of equipment.

The second part is called “after experiencing virtual reality”. Here we suggest an activity which should be done in a group framework, as long as there are a few people to participate. It goes without saying that this activity can only be done by people who have completed the first part (and have seen the VR story). In this second part we essentially deal with the application of the logical model of the project as presented in previous section.

To the second part we have added another, third phase, which inevitably focuses on the evaluation. It is called “integration: evaluating participants from participating in the VR experience.”

The issue of evaluation is very important and is related to the also important problem of effectiveness (of a program, a method, etc., Karalis, 2005, Stamboulis, 2017). Regarding the issue of evaluation, we expose the following thoughts:

• The “performance” of the participants –by saying performance we do not simply mean their satisfaction (“I liked it/I did not like it”, without explaining why), which, of course, is fully necessary – can be evaluated by the educators at the end of the activity according to the objectives/criteria, which were set out in the section on the project’s logical model, as well as throughout the present chapter, or in accordance with any other specific objectives (see the paragraph “criterion of success” below). A general conclusion about “how it went” can be communicated to the participants at the end. In any case, it is commonplace in the literature that assessing the acquisition of socio-emotional skills is very difficult and should be done carefully. In our case, it is not easy to understand if a student is really moving towards change, approaching it, achieving it, etc. This is very likely, of course. And we may have relevant clues every day, beyond what we have seen our students say and during “the lesson” (direct outputs). It is true that in general the behavior of the prisoner in the school, in the prison itself, etc., can provide such indications (medium-term outcomes). Of course, the most important indication of success (impact) is life after release (=avoidance of recurrence). This does not mean that any improvement already during the time of incarceration is not a significant priority ((medium-term outcomes). As it is understood, therefore, it is good to distinguish between direct outputs, medium-term outcomes and long-term impact.

• Based on the same criteria, participants can evaluate themselves. This increases their ability to think and also helps the educator to continue.

• Teachers themselves can evaluate their teaching by taking into account the various other assessments (of students, etc.) and by reflecting on questions such as: “What was good, what was bad, what went well in the activity and what did not? How did I feel? “

• Any kind of evaluation is important for the continuing use of the method by the educator and for how further planning should be done. We recommend that the educator deal deeply with this process, as well as record a lot of information (for example, through his own observation, or by collecting the answers of the students), since it is based on this material that he can be a researcher of his/her own work.

• To help assess “what the students learned” we included in the third part a series of short activities. The activities are much focused and therefore can be used as the main assessment tool for learners. They should be included in the design.

• It is very important to evaluate the educational program both in part and in its entirety after its completion. Here we must mention the so-called counterfactual impact analysis, which would show how and how much the program helps in the real change of prisoners, especially after release (by comparing some who used the STEPs method with others who did not use it). This certainly requires long-term research planning, which is not within our intentions. In fact, this is very difficult, especially in the education of prisoners.

Main criterion of success

We consider it appropriate to dedicate a paragraph here to define what will show us that the team as a whole and its members individually “did well”, what is the criterion of success (if we can use this expression).

It is obvious that our method does not seek to find a “correct answer”, since it is not about learning a language or math exercises. The only answer that can be considered correct (and this is not necessary, either) is for the trainees to design and present a life plan for the person in the story they watched where crime has gone from the foreground, where the person acts and acts for their own good and for the good of society, where decisions are far from delinquent behavior. However, in this context, since there is no black and white in life, many proposals can be made, as long as the emancipation of our student from crime is visible and clear.

The construction, therefore, of a robust life scenario with these characteristics is the direct result of the method we seek.

Important remarks

Our suggestions that follow in the following pages are a guide and a source of inspiration for the instructor and are adapted or differentiated according to the context each time or the content of each VR story. It is a range of actions. The method is distinguished by a variety of flexibility. For example, it is possible to confine to only one story (to a single activity), if e.g. there is no time. Also, the educator can work with a single student, because there is only one piece of equipment or because just one student wishes to implement the method.

So, if we confine to only one story -either with one person or with a group of persons- it is wise to pursue all the activities proposed here. But if we perceive the STEPs method as a full program comprising of 6 sessions (which is our desire), we should – whether working with one person or a group- apply all the activities suggested here at the first session, but in the remaining sessions we can choose some of them (or create new ones, similar to them). However, always remember that, for the remaining sessions, steps 1, 2, 5, 6, 7 of the second part and one of the activities of the integration phase are absolutely necessary.

As it will be understood when reading the following pages, the content of our proposals should be considered indicative to some extent. This means that it can be modified depending on the occasion. For example, in the first (individual) activity of the first part (remember that the first part has the role of introduction and preparation) it is not necessary to do all the exercises (SWOT, SMART etc.) and we can only be limited to the table.

Moreover, it should be noted that the duration of the above activities cannot be prescribed, as long as all this is not a test. This is a parameter that will depend on the practice and on those involved. Finally, an important parameter that should concern foremost the educators and their teams are issues related to prison culture: the prison world is not the same as the “outside” world, given that, according to our experience, the multiple distortions of “outside” society, such as various divisions, inequalities, contrasts and other problems, are being exacerbated inside the prison. We do not need to expand further here on these issues, which so far have not bothered research a lot. Let us, however, insist on the issue of gender, which, especially in men’s prisons, may take a frightening dimension. Therefore, some male inmates may not want to deal with our so-called “women’s” stories, and this is a completely respectable right of theirs. Of course, the opposite also occurs. As mentioned above, the educator and their teams are free to decide on a case-by-case basis, regarding not only this, but also many other issues.

show less

You can find the full guide here.